Concepts of Inequality

Introduction

- Inequality is a multifaceted term with various interpretations.

- Oxfam International classifies it into economic and social inequality, which are interconnected.

- Nobel Laureate economist Amartya Sen highlights its centrality in social theory.

Social Inequality

- Social inequality involves the uneven distribution of resources based on categories like power, religion, kinship, race, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, and class.

- It can manifest as unequal outcomes or a lack of equal access to opportunities.

- Social inequality is often tied to economic inequality through income and wealth distribution.

Economic Inequality

- Economic inequality is characterized by an unequal distribution of income and wealth within and between countries.

- Concentration of economic power in the hands of a few exacerbates inequality.

- The pandemic has widened economic disparities, favoring the already affluent.

Global Perspective

- Wealth is increasingly concentrated in private hands, surpassing government wealth.

- Governments are losing assets, making them vulnerable to economic shocks.

- A significant portion of the world’s population lacks the wealth for a decent life.

The World Inequality Report 2022

- The top 10% of the global population collectively owns 76% of total wealth, while the bottom 50% owns just 2%.

- India is among the most unequal countries with high poverty rates and a significant number of billionaires.

- The richest 10% in India control 64.6% of the country’s wealth, while the poorest have a meager 5.9%.

- The middle class, comprising 40% of India’s population, faces economic challenges.

Gender and Global Inequality

- Gender inequality contributes to economic disparities.

- Women’s earnings are limited, affecting overall wealth.

- Liberalized economic development has primarily benefited the wealthiest 1%.

Conclusion

- Inequality, encompassing social and economic aspects, persists globally.

- The World Inequality Report highlights extreme wealth disparities.

- India’s socioeconomic policies contribute to high inequality.

- Gender-based economic disparities and unequal wealth distribution exacerbate the problem.

Addressing inequality remains a crucial challenge for society and policymakers worldwide.

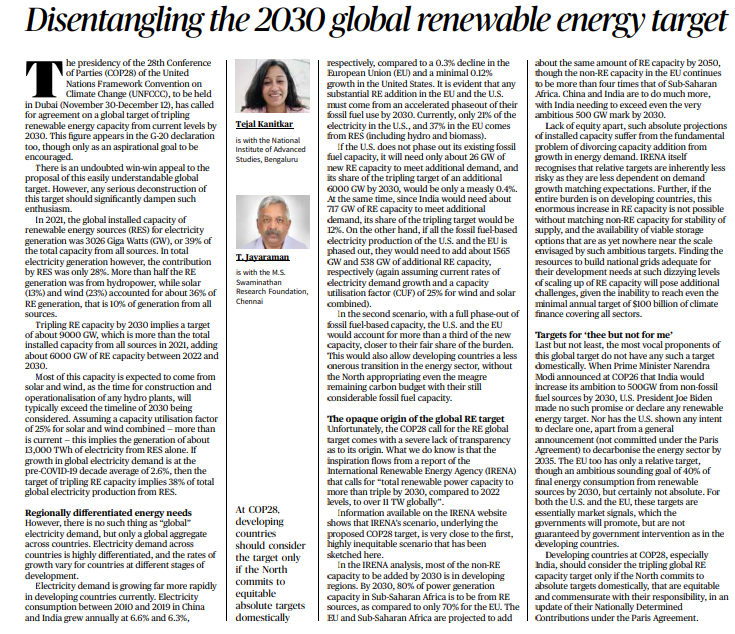

GLOBAL RENEWABLE ENERGY TARGETS

Introduction:

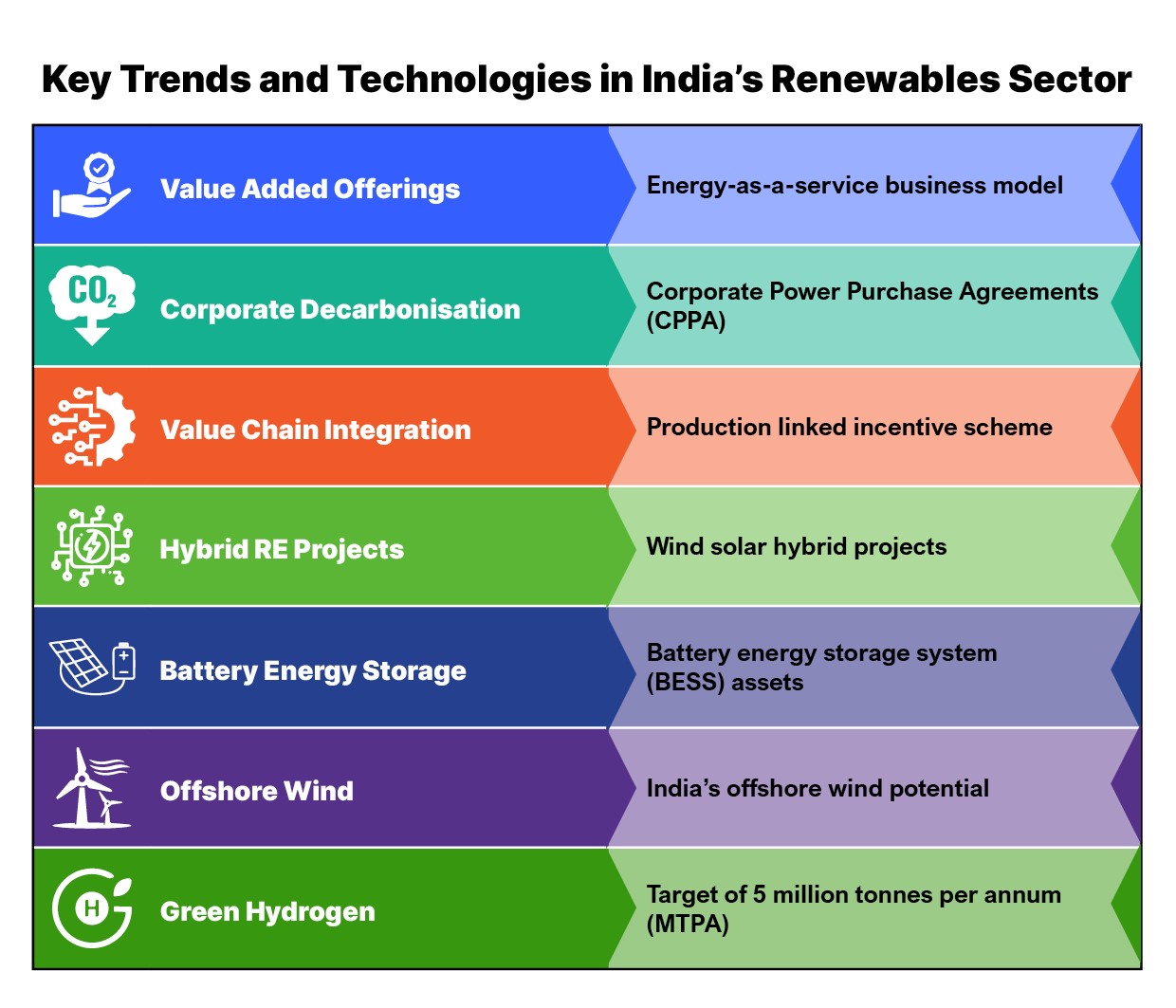

- The 28th Conference of Parties (COP28) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), scheduled to be held in Dubai from November 30 to December 12, has called for a global agreement to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030.

- This target also appears in the G-20 declaration but only as an aspirational goal.

The Challenge of Tripling Renewable Energy Capacity:

- In 2021, global installed capacity for renewable energy sources (RES) for electricity generation stood at 3026 GW, contributing 39% to the total capacity from all sources.

- However, RES contributed only 28% to total electricity generation, with hydropower, solar, and wind accounting for 36% of RES generation.

- Tripling RE capacity by 2030 would require adding about 6000 GW, which is more than the total installed capacity from all sources in 2021.

Energy Generation Implications:

- Assuming a capacity utilization factor of 25% for solar and wind combined, achieving this target would result in generating about 13,000 TWh of electricity from RES alone.

- This would constitute 38% of total global electricity production.

However, this target fails to account for regional differences in energy needs and growth rates.

Regional Differentiation in Electricity Demand:

- Electricity demand varies significantly among countries and regions. Developing countries, particularly China and India, are experiencing rapid electricity demand growth, while growth in the European Union (EU) and the United States is much slower.

- Meeting the target would require the EU and the U.S. to accelerate the phaseout of fossil fuels, whereas India would need to add a substantial 717 GW of RE capacity.

Equity and Burden-Sharing:

- To ensure equity, it is crucial that developed countries like the U.S. and the EU phase out their existing fossil fuel capacity.

- In this scenario, they would need to add significant RE capacity, which would be closer to their fair share of the burden.

- This approach would also allow developing countries to transition with less burden and without depleting the remaining carbon budget.

Lack of Transparency in Target Origin:

- The origin of the proposed RE global target lacks transparency. It is inspired by a report from the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), which calls for renewable power capacity to triple by 2030 to over 11 TW globally.

- IRENA’s analysis is close to an inequitable scenario that heavily relies on developing regions to contribute most of the non-RE capacity.

Capacity Addition vs. Energy Demand Growth:

- Absolute projections of installed capacity, divorced from growth in energy demand, pose risks.

- Relative targets are considered less risky as they are less dependent on matching demand growth expectations.

- Achieving the proposed target would also require substantial non-RE capacity for supply stability and viable storage options, along with the resources to build national grids adequate for development needs.

Lack of Domestic Commitments:

- Notably, proponents of the global target, such as India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, have announced domestic targets, but major players like the U.S. and the EU lack absolute renewable energy targets.

Their goals are more market-driven, not guaranteed by government intervention as in developing countries.

Conclusion:

Developing countries, especially India, should only consider the tripling global RE capacity target if developed nations commit to absolute and equitable domestic targets commensurate with their responsibilities under the Paris Agreement. The lack of such commitments raises concerns about the fairness and feasibility of achieving this ambitious global goal.

BHARAT'S JOURNEY TO ECONOMIC GROWTH AND INNOVATION: THE ROAD AHEAD

Introduction

- Bharat (India) has achieved the remarkable feat of becoming the world’s fifth-largest economy and is poised to ascend even higher, aiming for the third spot.

- However, it faces significant challenges in the realms of innovation, science, and technology. This deficit can be attributed partly to the underperformance of Indian academia and industry in contributing to national research and development (R&D) efforts.

- Additionally, hindrances in fundamental factor markets such as land, labor, and capital, coupled with flawed trade policies, have impeded progress in key manufacturing sectors.

Current Progress and Momentum

- Despite these challenges, Bharat has made substantial strides. The ‘Make in India’ initiative has gained momentum, with the country’s share of global merchandise exports reaching new highs.

- Recognizing the need for a robust innovation ecosystem, the government is streamlining the patent generation process.

- Bilateral agreements, particularly with the United States, underscore the strategic importance of science and technology, emphasizing that ‘Invent in India’ must complement ‘Make in India.’

The Role of National Research Foundation (NRF)

- The recently established National Research Foundation (NRF) is expected to play a pivotal role in addressing critical issues hindering innovation.

- To achieve its ambitious economic goals, India must restructure institutions responsible for channeling resources and scientific knowledge into technology-based wealth creation.

- These reforms are crucial because, despite its vast human capital, India has underperformed in science and technology.

Critical Parameters for Overhaul

- Quality over Quantity in Human Capital

- To staff and administer institutions effectively, emphasis must be placed on the merit and quality of human capital. Scientific research adheres to Lotka’s law, where a few top leaders in a field are paramount.

- Retaining top talent domestically and attracting international talent should replace the remittance-focused mindset of the past.

- Integrating teaching and research, with collaborations between government labs, universities, and science parks, should be encouraged to create a merit-driven admissions system.

- Barbell Strategy for Funding Research

- Implement a barbell funding strategy that supports high-risk, high-reward projects through collaboration between government agencies and industry.

- Models like the New Millennium India Technology Leadership Initiative (NMITLI) and the Design-Linked Incentive (DLI) program, which fostered industry-academia collaboration, serve as reliable benchmarks.

- Encourage individual researchers to seek supplemental funding from industry for moon-shot research while creating joint government-industry initiatives for blue-sky research.

- Cultural and Software Reboot

- Beyond institutional changes, the culture and ethos of Indian science require transformation.

- Reevaluate the influence of science bureaucrats and domain experts in academia to prevent self-perpetuation and foster innovation.

- Emphasize the importance of impartial peer review and stimulate controlled risk-taking.

- Recognize that the quality and motivations of those involved in Indian science are pivotal for long-term success, with implications not only for economic progress but also national security.

Conclusion

Bharat’s ascent to becoming a global economic powerhouse depends on its ability to bridge the innovation and technology gap.

Through a multifaceted approach, which includes focusing on the quality of human capital, a balanced funding strategy, and a cultural shift in scientific circles, Bharat can unlock its vast potential.

The establishment of the NRF provides hope for catalyzing these essential reforms and achieving the nation’s economic aspirations in the coming decade.

Embracing Carbon Trading for India's Sustainable Future

- This system allows organizations to buy and sell carbon credits, enabling those with low emissions to offset those with higher emissions, and it has the potential to play a crucial role in India’s efforts to combat climate change.

Carbon Credits: A Temporary “License” for Emissions

- Carbon credits can be thought of as temporary “licenses” for organizations to emit a specific quantity of CO2 in a given year.

- This mechanism enables companies with low emissions to sell their excess credits in the market to those willing to pay for them.

- This practice offsets the emissions of entities struggling to meet emission reduction goals, either due to regulatory mandates or internal sustainability targets.

The Indian Carbon Market (ICM): A National Framework

- India is planning to establish the Indian Carbon Market (ICM), a national framework for carbon credit trading, to facilitate the decarbonization of its domestic economy.

- The Indian Carbon Credit Scheme 2023 draft framework has been recently notified by the Union government, with the Bureau of Energy Efficiency and the Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change collaborating on its development.

The ICM’s Potential Impact

- The Indian government believes that the ICM will mobilize investments for transitioning to a low-carbon ecosystem.

- It aims to reduce India’s emissions intensity of GDP by 45% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels, aligning with its global climate commitments under the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC).

Greater Scope for Energy Transition

- While India already has an energy savings-linked market mechanism, carbon credit trading can broaden its scope by covering a wider range of energy segments.

- GHG emissions intensity targets and benchmarks will be developed in accordance with domestic emissions trajectories, aligning carbon credit trades with sectoral performance.

Regulatory Oversight and Innovation

- The current draft notification lacks specific provisions for the functioning of carbon markets.

- Regulatory oversight responsibilities will be vested in a National Steering Committee chaired by the Secretary, Ministry of Power.

- As India aims for net-zero emissions by 2070, the ICM will offer flexibility to hard-to-abate industries, encouraging them to increase their GHG emission reduction efforts through carbon market credits.

Mobilizing Funds and Fostering Innovation

- The ICM has the potential to attract finance and technology for sustainable projects that generate carbon credits, making it a significant source of funds for the low-carbon transition.

- Additionally, the introduction of a carbon pricing mechanism will encourage businesses to consider environmental impact in their strategic decisions, driving investments towards low carbon footprint practices.

International Implications and Regulatory Oversight

- As carbon-related tariffs like the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) begin to impact trade, businesses must consider both national and international implications.

- This necessitates close regulatory monitoring of the carbon credit market to ensure its smooth operation.

Industry Leaders in Carbon Management

- Industry leaders specializing in carbon management solutions and clean energy transition can play a pivotal role in India’s transition to a net-zero future.

- Their expertise can help shift the nation away from fossil fuels and legacy technologies toward clean energy systems.

Conclusion

India’s journey toward balancing economic needs and environmental concerns requires innovative solutions. A vibrant carbon trading mechanism, exemplified by the Indian Carbon Market, can be instrumental in creating a more sustainable future.

As the country strives for a net-zero world, carbon credit trading has the potential to catalyze emissions reduction efforts, encourage investments in low carbon practices, and position India as a leader in sustainable development.