1. Adapting Carbon Finance Standards for India's Agroforestry: Challenges and Opportunities

Introduction

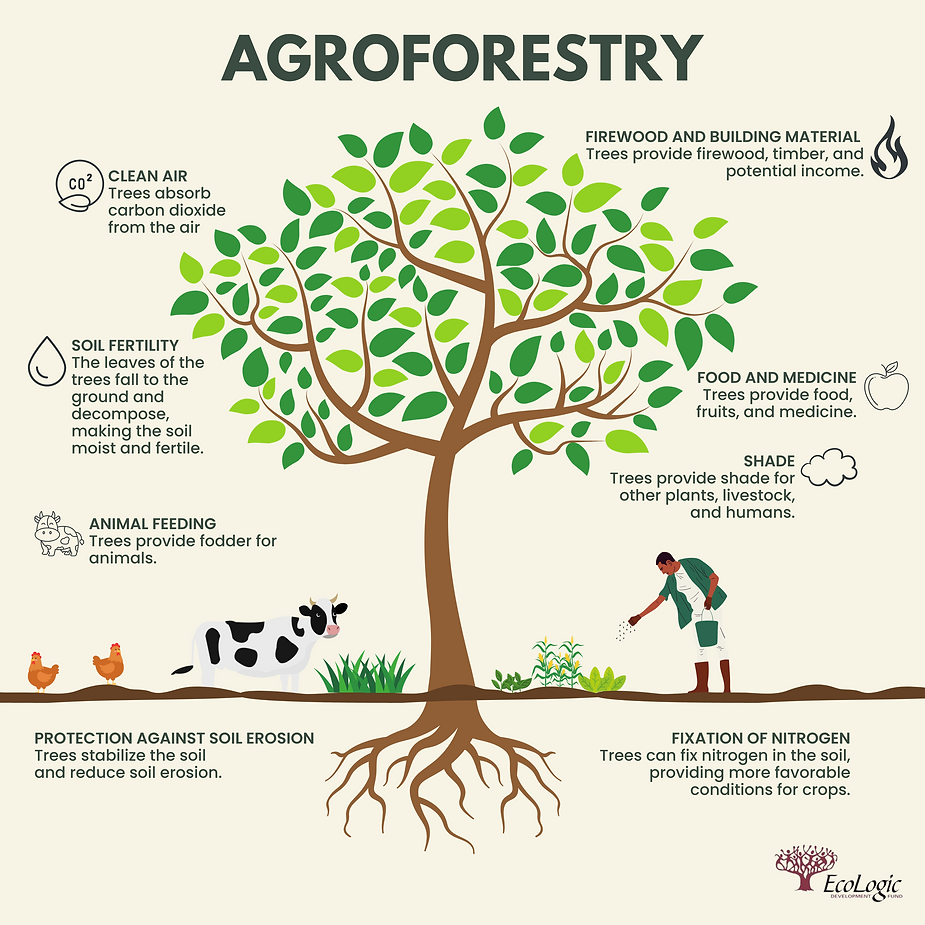

- Agroforestry in India has the potential to play a pivotal role in carbon finance projects, particularly through Afforestation, Reforestation, and Revegetation (ARR) initiatives. India’s current agroforestry area is around 4 million hectares but has the potential to expand to 53 million hectares by 2050.

- This sector is significant for its contributions to environmental sustainability and economic development, accounting for 65% of India’s land area and contributing 19.3% of the country’s carbon stocks.

Common Practice in Carbon Standards

- Definition: The concept of “common practice” in carbon standards refers to whether an activity goes beyond what is typically done in a given region.

Significance in ARR Projects: For ARR projects, an activity must exceed common practice to qualify for carbon credits, meaning it should demonstrate additional environmental benefits beyond the norm.

Challenges in Applying Global Standards to India

- The global definition of “common practice” is problematic for India’s fragmented agricultural landholdings, where the average land size is significantly smaller than in regions like Latin America or Africa. This restricts Indian farmers from qualifying for carbon credits under current standards.

- Data Insight: 1% of Indian farmers are small and marginal, with holdings often less than two hectares.

India-Centric Approaches for Agroforestry

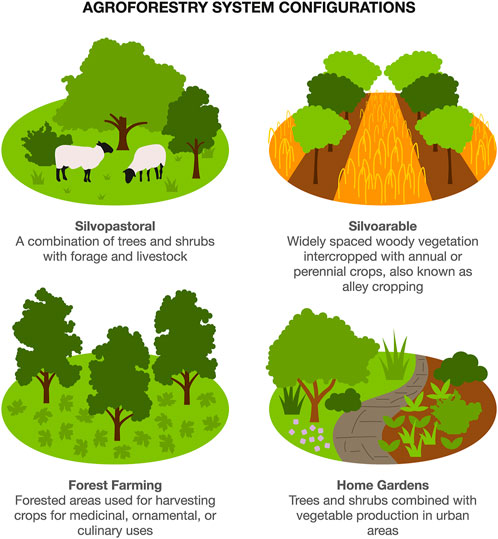

- Given India’s unique agricultural landscape, there is a need to revise the global carbon standards to reflect the realities and opportunities within India’s agroforestry sector.

- India-specific solutions would allow small and marginal farmers to:

- Benefit from carbon sequestration.

- Gain economic benefits while enhancing soil fertility, water retention, and combating erosion.

Helping Small and Marginal Farmers

- The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) has already launched 19 projects benefiting 56,600 farmers, emphasizing the potential of ARR projects to uplift small farmers.

- To further integrate more farmers, international carbon finance platforms need to evolve their guidelines, recognizing India-specific challenges such as:

- Small landholdings.

- Fragmented agricultural landscapes.

- Diverse cropping systems.

Need for Revisions in Carbon Credit Platforms

- International platforms like Verra and Gold Standard should:

- Revise their standards to accommodate the potential of small-scale, India-specific agroforestry initiatives.

- Recognize small agroforestry projects as significant contributors to global sustainability efforts.

Conclusion

- India’s agroforestry sector holds vast potential to contribute to global carbon sequestration efforts while providing economic benefits to small and marginal farmers.

- However, this potential can only be fully realized if international carbon finance platforms adopt more flexible standards that reflect the realities of Indian agriculture.

- By doing so, India can leverage agroforestry not only for environmental sustainability but also for rural economic upliftment.

Mains Practice Questions

|

Q. “Discuss the potential of agroforestry in India in contributing to carbon sequestration and how international carbon finance standards could help small farmers.”

|

2. Global Inequality and International Governance

Introduction

- The Summit of the Future highlights fundamental questions related to global governance, particularly focusing on power imbalances in institutions, agenda setting, and rising global inequalities.

- The summit aimed to tackle ongoing global issues through a Global Digital Impact Initiative and a Declaration on Future Generations, emphasizing the need for enhanced cooperation and multilateral action.

Global Inequality and Governance Challenges

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Recent data from the UN indicates that only 17% of the SDGs are on track. This highlights a significant gap between developed and developing countries in terms of achieving economic and social progress.

- Example: Developing nations collectively hold $9 trillion in public debt, with over $847 billion paid annually in interest. In 2022, they experienced a negative net resource transfer.

- Global Power Imbalances:

- G7 Dominance: The G7—which comprises major developed economies—still sets the global agenda, despite the rise of emerging economies like China and India.

- Historical Context: The G7, formed in the 1970s, mirrors a Western-centric order rooted in post-World War II geopolitics. However, the summit recognized that developing nations still face an uphill battle in having their voices heard on global platforms like the UN Security Council.

Economic Shifts and Multilateralism

- Economic Shifts: The rise of China and India, alongside the BRICS grouping, signals the beginning of a more multipolar world order. However, colonial-era economic imbalances still weigh heavily on many nations.

- Historical Perspective: In 1950, the U.S. consumed 40% of the world’s natural resources. By 2023, the West’s dominance has shifted, but developing nations still face barriers to full economic participation.

- Decline of Western Influence:

- The G7’s influence has decreased significantly, with its global share of resources falling from 40% in 1950 to 26% in 2023. Yet, multilateralism remains dominated by the Western bloc, even as new powers like Asia emerge.

- Example: Despite growing influence, South Africa’s efforts to influence climate negotiations in 2023 were hindered by the climate regime, indicating the persistence of Western hegemony.

Challenges in Multilateral Cooperation

- Multilateralism vs. Unilateralism: The failure of the Summit to outline a clear path for Security Council reform underlines the challenges in modernizing global institutions to reflect new economic realities.

- Developing Countries: Developing nations struggle with under-representation in key decision-making bodies like the UN and IMF, limiting their ability to shape global policies.

- Role of Experts in Governance:

- The Summit emphasizes a growing trend where global governance issues are increasingly driven by “expert opinions” rather than democratic consensus, as seen in areas like Artificial Intelligence and GDP modification.

Foundations of Power

- The balance of power historically centered on Western dominance—from the 1800s through the 20th century—but has increasingly shifted toward Asia and other emerging regions.

- Shifting Energy Consumption: By the 21st century, the West was consuming the same amount of energy as the rest of the world combined in the 1950s, underscoring the shift in global consumption patterns.

- Technological Imbalance: The disparity in technology and endogenous development further cements global inequalities, limiting the capacity of developing nations to compete on equal footing.

Conclusion

- The Summit of the Future underscores that while global shifts are occurring with the rise of new powers, systemic inequalities remain entrenched in economic, geopolitical, and institutional hierarchies. Addressing these disparities will require reforms in global governance structures, including UN representation, revised economic frameworks, and a focus on justice and equality in international decision-making processes.

- The future of global governance must prioritize inclusive development, allowing developing nations to fully leverage the opportunities within the existing system.

Mains Practice Questions

|

Q. “Discuss the role of global institutions like the UN and IMF in perpetuating or addressing global inequalities. How can these institutions be reformed to reflect the current global economic order?”

|